Mobilising for mass release of guard bees in Apis dorsata

H.K. Käfer and G.K. Kastberger

Zoologie, Karl Franzens Universität Graz, Graz, Austria

The South Asian Giant Honeybee Apis dorsata builds single-combed nests in the open, attached to branches, rocks or buildings. The bees themselves cover the comb in several living layers, forming a so-called bee curtain. The nests are exposed to the weather and to predators feeding on bees. The pressures of predation, particularly by birds and wasps, have induced the evolution of defence strategies [1]. Responding to predatory wasps, members of the outer layer display so-called shimmering behavior [2]. Stronger stimuli, e.g. from birds, may provoke a mass attack [3]: within a fraction of a second, hundreds of bees take flight to attack the enemy and pursue it over a large distance. The current study examines how a colony mobilizes itself to provide such a sudden defence response.

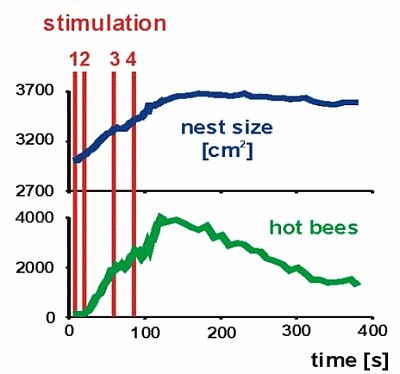

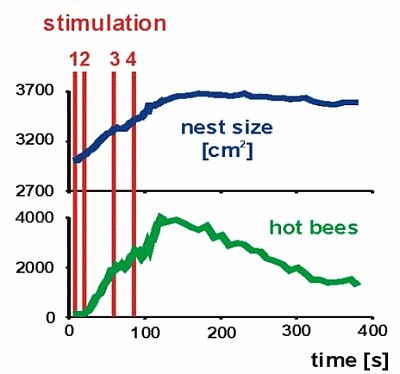

In our experiments, we disturbed Apis dorsata nests by throwing small twigs towards the centre of the nest. The nest surface was monitored by infrared camera (Thermacam SC1000), so that changes in the temperature of single individuals as a response to stimuli could be assessed by image analysis. After the stimulus, guard bees were recruited in the disturbed area of the nest. On one hand, formerly quiescent surface bees started warming up their thoracic muscles; on the other, nest-warmed bees with an overall body temperature of 37°C emerged from inside the nest (Figure 1, lower curve). These individuals may be called soldier bees, as they were not previously members of the surface layer and were specially recruited for defence.

Figure 1. Changes in nest size and the number of hot bees following stimulation.

The group of hot bees assembled at the nest surface was uniquely responsive. Consecutive stimuli triggered the immediate release of some of the recruited bees. Seconds after the stimulus, the nest started to increase in size (Figure 1, upper curve). Two responses can be distinguished here: initially, the bee curtain became vertically longer, reflecting movement only in the vertical mesh component of the bee curtain. This can be seen as an active response of bees in the mesh of the curtain layers, which stretch their legs to make room for bees emerging from inside the nest. In a second step, the emerging bees force the mesh of the curtain to disperse in a horizontal direction.

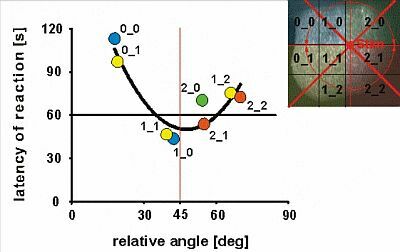

The response latency of any particular zone of the nest surface (measured as the time interval between the moment of disturbance and the onset of soldier bee emergence) depends on its distance and angle from the stimulation site. Arousal spreads faster diagonally than it does horizontally or vertically (Figure 2). We assume that the three pairs of legs of the curtain bees form the network for signalling arousal state, as individuals are 'connected' to each other via their fore- and midlegs [4].

Figure 2. The relationship between response latency and relative angle from the site of stimlation.

References

Paper presented at Measuring Behavior 2002 , 4th International Conference on Methods and Techniques in Behavioral Research, 27-30 August 2002, Amsterdam, The Netherlands