Karl Bates

Measuring functional morphology and ecological behaviour during the evolution of birds

Wednesday 6th June 17:00 - 18:00, G27

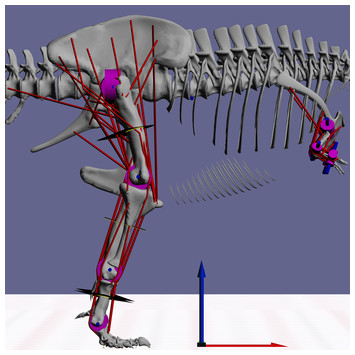

Birds are one of the most taxonomically and ecologically diverse groups of vertebrates in modern ecosystems. Extant birds also possess a number of highly specialized and in some case unique morphological characteristics, including feathered bodies, wings, a hypermobile neck, and a highly pneumatised skeleton associated with a system of rigid air sacs. These novel morphological features are intrinsically linked to specialized functional traits of birds, notably powered flight, the use of unusual “crouched” bipedal postures during walking, and a unique system of lung ventilation. When and how these morpho-functional specializations evolved, and the extent to which they are interlinked, represent major questions in palaeobiology. In this talk, I will review recent research into the ‘evolutionary biomechanics’ of bird evolution. This research area is facilitated by a rich fossil record, which details the gradual step-wise acquisition of derived avian morphologies (and by inference mechanics and physiologies) during the Mesozoic Era. Recent work using computer models has demonstrated how temporal and phylogenetic changes in body shape (i.e. mass distribution) and muscle leverage effectively trace the gradual shift from the erect bipedal postures used by basal dinosaurs to the more unusual crouched (‘zig-zagged’) limb posture seen in extant birds. Quantitative analysis of bone shape reveals unique patterns of morphological regionalization within the necks of living birds, which correlate with variation in the degree of mobility within the neck. As with body shape and limb muscle evolution, evolutionary changes in neck form-function appear to intensify in extinct theropod dinosaurs close to the evolution and diversification of animals with powered flight capability. This strongly suggests that whole-scale changes in morpho-functional anatomy were crucial to the evolution of powered flight and that many novel avian features may well be highly interlinked. Expanding and refining our understanding of this important ecomorphological transition is likely to be challenging, but immediate leaps forward will be realized by further work on extant taxa and the continued development of computer simulation approaches for reconstructing biomechanical performance in extinct animals.

Karl Bates

Dr Karl Bates is a lecturer in musculoskeletal biology at the University of Liverpool. His research concentrates on the functional anatomy of terrestrial vertebrates, with a particular focus on the locomotor system. His goal is to understand the links between morphology (both hard and soft tissues) and biomechanics in order to better characterize how animals achieve their full range of habitual motions and behaviors. He routinely uses a range of theoretical and experimental techniques to study locomotion, ranging from motion analysis, force and pressure platforms to 3D static and dynamic computer simulations Using these techniques to study form-function relationships in living animals forms the basis of his research into the biomechanics of extinct (fossilized) animals. His biomechanical reconstructions of extinct taxa enable the functional consequences of changing morphology seen in the fossil record to be understood in a wider behavioral and ecology context, providing insight into the selective pressures and constraints acting on organisms over deep time. This has led him to study a range of tetrapods from primates (particularly humans and other Great Apes) to archosaurs (birds, crocodilians, and dinosaurs) in order to further our understanding of major evolutionary transitions in biomechanics and behavioral ecology.

.jpg)